The news of

Robert Creeley’s death arrived last March via an email from Michael Rumaker, forwarding the stark note he’d received from his friend Henry Ferrini: “Bob Creeley died this morning in Odessa, Texas with his wife and kids by his side.” Other email confirmed the sad truth. I was stunned; I hadn’t physically seen him for several years, but, notwithstanding his age (he was ((

only, I want to say)) 78), by all accounts he had continued to be robust and active, and his last book (for now),

If I Were Writing This…, published in 2003

, had contained stunning, vital work. I’d kidded him via email on his previous birthday that I didn’t think he’d peaked yet (as though that would have meaning in the sport of language), and I’d looked forward to seeing him this summer, confident that we would continue our intermittent conversation of some thirty years. But then he was gone, brought down in Texas; it’s yet another thing that Texas must answer for.

Driven by his puritan’s sense of duty to continue in spite of illness, he had pushed on until his body told him he could not, and stopped.

The plan is the body.

Who can read it.

(from “The Plan Is The Body”, Selected Poems [1976])

Less than a year later, it’s not time yet for me to assess his long career or his work in all its complexity, in all its various detail. It does seem possible, even necessary, though, to sketch some of the directions in his poetry. He was one of a handful of poets who reinvented American poetry at the middle of the last century, so it’s essential, if we want to understand where we are as writers and readers of poetry, to have some sense of what he did. His early poems, with their echoes of troubadour lyric, Elizabethan in their sense of nuance and intellectual grace, were already unique. And then he got really adventurous. He could explore the meaning of a word in various conditions with the best of his peers, and as well as the poets he considered his masters, like Olson and Williams, but he also wrote with heart. Though I can’t find the reference now (perhaps I’ve imagined it, though I’m not yet convinced), I remember his Black Mountain College fellow Ed Dorn writing of Bob’s early work as the “consummate articulation of feeling”. Not feeling in some sentimental sense, some recapitulation of sanctioned expression, but of feeling as felt, as actual, as practiced, with rare honesty. Here’s something I’ve always liked from For Love, published in 1962, his first book to have publication of more than a few hundred copies, though he’d been writing since 1945. It’s called “The Name”, and is addressed to his daughter:

Be natural, wise

as you can be,

my daughter,

Let my name

be in you flesh

I gave you

in the act of

loving your mother,

all your days,

her ways,

the woman in you

brought for

sensuality’s measure,

no other,

there was no thought

of it but such

pleasure all women

must be in her,

as you. But not wiser,

not more of nature

than her hair,

the eyes

she gives you.

There will not be another

woman such as you

are. Remember

your mother,

the way you came,

the days of waiting.

Be natural,

daughter, wise

as you can be,

all my daughters,

be women

for men

when that time comes.

Let the rhetoric

stay with me

your father. Let

me talk about it,

saving you such

vicious self-

exposure, let you

pass it on

in you. I cannot

be more than the man

who watches.

There were grittier poems also, of course, given that the years of For Love’s composition included the end of his first marriage - poems like the trenchant “Ballad of the Despairing Husband”, which readers should forthwith find for themselves, given its length. Here are its opening stanzas:

My wife and I lived all alone

contention was our only bone.

I fought with her, she fought with me,

and things went on right merrily.

But now I live here by myself

with hardly a damn thing on the shelf,

and pass my days with little cheer

since I have parted from my dear.

Oh come home soon, I write to her.

Go fuck yourself, is her answer.

Now what is that for Christian word?

I hope she feeds on dried goose turd.

If you had any immediate experience of the fifties, you know that was wild, far out, and totally rad for the era.

His next book, Words, moved deeper in its exploration of the significance of person, the phenomenology of self, and asked more explicitly what it meant to be an I, a creature of apparently singular identity, as in “The Pattern”:

As soon as

I speak, I

speaks. It

wants to

be free but

impassive lies

in the direction

of its

words. Let

x equal x, x

also

equals x. I

speak to

hear myself

speak? I had not thought

that some-

thing had such

undone. It

was an idea

of mine.

With Pieces, published in 1969, he went further than even Williams had to demolish the poem as a received form – or “deconstruct” it, as we might now say. He opened up poetic form, dismantled it, and explored the intersections of poetry with other modes of speech. It’s a sustained meditation on the act of thinking, of acting otherwise, and the mystery of perspective – just for starters! Here are a few of the initial pieces:

No one

there. Everyone

here.

….

The Family

Father

and mother

and sister

and sister

and sister.

Here we are.

There are five

ways to say this.

….

Kate’s

If I were you

and you were me

I bet you’d

do it too.

Merce Cunningham came in his choreography to ponder that the stage as defined by traditional proscenium had “front” and “back”, and realized that in fact wherever the dancer moved was the front of his/her stage, the place of his or her act, and so found it necessary to redefine the presentation of dance. In a similar way Creeley set out to build a reality for the poem that recognized as “front” the location of the voice which spoke it, and the locations at their own fronts of other selves and proximate figures otherwise involved.

There are five/ways to say this.

In another piece of these Pieces, one found in “Mazatlan: Sea”, there’s this:

Want to get the sense of “I” into Zukofsky’s “eye” – a locus of experience, not a presumption of expected value.

In a poem of the social world, this concern could manifest as it does in the first sections of “The Friends”:

I want to help you

by understanding what

you want me to

by saying so.

.

I listen. I had

an ego once upon

a time – I do still,

for you listen to me.

Let’s be very still.

Do you hear? Hear

what, I will say when-

ever you ask me to listen.

While such use of dialogue with ambiguous speakers was adumbrated in several poems - “I Know a Man”, for example – of For Love, Pieces explores the territory more deliberately, with more verve, and goes further.

Also appearing explicitly in Pieces was another concern that Creeley articulated in various ways through his subsequent work: the role of language in creating the world we know. As he notes in “Zero”, the last of a series named “Numbers”;

There is no trick to reality –

a mind

makes it, any

mind.

Or the same series, in “Two”:

This point of so-called

consciousness is forever

a word making up

this world of more

or less than it is.

In his readings during the 1990s, Bob often referred to the story told by the English philosopher Bertrand Russell concerning a conversation he, Russell, had had with Ludwig Wittgenstein, who was then attending his seminars and classes. “He thinks nothing empirical is knowable - I asked him to admit that there was not a rhinoceros in the room, but he wouldn't." Russell, so the story goes, then set about searching the room, lifting the skirts of sofas and chairs, in an effort to prove to Wittgenstein that indeed there was no rhinoceros in the room, ignoring entirely the linguistic fact that there was, indeed, a rhinoceros in the room, and he had created it.

Pieces embodied a reconstruction of form and a reconsideration poetic voice that sent tremors through the world of writing that ripple still, that raised questions those of us concerned with how thought works, and how language limns the world, still address. It became evidence in itself of a transformation Bob marks in another of its poems:

Diction

The grand time when the word

were fit for human allegation,

and imagination of small, local

containments, and the lids fit.

What was the wind blew through it,

a veritable bonfire like they say –

and did say, in hostile, little voices:

“It’s changed, it’s not the same!”

Not, certainly, that Bob was working alone. Bob always thought of himself, as he often said, as part of a fellowship, a company of persons of like mind. Olson, his mentor, whose work he edited and for whose recognition he was always a determined advocate, had certainly helped clear the conceptual ground and offered a model of practice. Fellow Black Mountain poets Ed Dorn, Denise Levertov, and Robert Duncan, San Francisco’s Jack Spicer and Robin Blaser, and, of course, many of the Beats worked in parallel directions. No one, though, to my eye, got closer to the mind’s bone.

After Pieces

Creeley was always prolific, whatever might be transpiring in his personal life, and wherever life might find him engaged. Over the next three and a half decades he published nine collections of poetry (not counting chapbooks and very small press editions); three additional volumes that collected work between given dates, including the Collected Poems 1945-1975 of 1982; and two Selected Poems, the second of which, published in 1991, contained his own selection of his work. In addition to the poetry, he published a novel, The Island, in 1963, a book of stories, The Gold Diggers, in 1965; these were included in the Collected Prose of 1984, which also included Mable: A Story, A Daybook, and Presences. His essays and critical pieces were first collected in A Quick Graph, published in 1970; the contents of that volume were included, with much other material, in The Collected Essays of 1989. He loved to collaborate with visual artists, and did so frequently, right through the “En Famille”, “Drawn & Quartered” and “Clemente’s Images” poems which appear in If I Were Writing This …. It’s an amazing body of work, however one measures it. The great critic and literary historian Hugh Kenner once noted that Creeley probably had no sense of which of his poems were his “best” works, because he didn’t think in such simple terms of value. He was assuredly right. In the preface to the early collection The Charm, Bob noted, citing Robert Duncan for the observation, that “poetry is not some ultimate preserve for the most rarefied and articulate of human utterances, but has a place for all speech and all occasions thereof. … Selfishly enough, I can often discover myself [in these poems] in ways I can now enjoy having been – no matter they were ‘good’ or ‘bad’.” In a career that spanned sixty years, Creeley certainly produced some poems that were “better” than others, especially if one takes that to mean that some are more immediately useful or accessible than others, or open larger worlds of more apparent significance. But as with the work of any major poet (and it’s clear that Bob was that), even the small, apparently lesser pieces can offer startling insights and bring us into moments of recognition, instances of the jewel mind caught in the net of its own facets, refracted with riveting clarity.

Over time he developed ways to address his persistent concerns that focused less on the formal structure of the poem as extensive activity of mind, and more on the larger issues (as he came to see them) of language and world, and of the experience we have of time, and time’s losses. The poems in If I Were Writing This …, the last book he published during his lifetime, appear to be, well, conventional. They evidence intensity, though, that is anything but ordinary. They distill a lifetime of learning about the task of being human, of being (in) a body that breaks down, as consciousness deepens and goes on. Here’s the first poem in the book:

The Way

Somewhere in all the time that’s passed

was a thing in mind became the evidence,

the pleasure even in fact of being lost

so quickly, simply that what it was could never last.

Only knowing was measure of what one could

make hold together for that moment’s recognition,

or else the world washed over like a flood

of meager useless truths, of hostile incoherence.

Too late to know that knowing was its own reward

and that wisdom had at best a transient credit.

Whatever one did or didn’t do was what one could.

Better at last believe than think to question?

There wasn’t choice if one had seen the light,

not of belief but of that soft, blue-glowing fusion

seemed to appear or disappear with thought,

a minute magnesium flash, a firefly’s illusion.

Best wonder at mind and let that flickering ambience

of wondering be the determining way you follow,

which leads itself from day to day into tomorrow,

finds all it ever finds is there by chance.

It’s aptly named, as Bob’s testament, his summary of his own Tao. I’ve read that poem many times now, and it gets richer and richer. It’s writing that matters, something to take with us down the road. And that’s what counts. The book’s other writing of equally sustained insight and engagement have made it, for me, an essential text.

To the end, Creeley wrote, as he had determined to early on,

The poem supreme, addressed to

emptiness ‑ this is the courage

necessary. This is something

quite different

From “The Dishonest Mailmen”, first published in The Whip, collected in For Love.

There’s not yet much to read about Creeley. There is his own “Autobiography”, included in Tom Clark’s otherwise indispensable Robert Creeley and the Genius of the American Common Place, still in print. There’s also a wonderful portrait of Bob at Black Mountain College, one of the major intersections in his life, in Michael Rumaker’s Black Mountain Days; it also features a richly resonant take on Charles Olson, Bob’s mentor and co-conspirator, and one of Rumaker’s teachers as well. Eckbert Faas’s disappointing Robert Creeley (2001) barely veils its adversarial approach, and covers in real depth only the first phase of Creeley’s career as poet. I suppose all of us who have married and divorced can expect the testimony of our former spouses to be featured in any biographies that it might occur to someone to write, but Ann MacKinnon’s memoir of her marriage to Bob is nearly the only thing included in Faas’ book that’s of substantial value – and it doesn’t reveal Creeley in the way Faas seems to think it does. Oh, well.

So read Bob instead. Most of his work is still in print, and there’s more to come: the University of California Press will issue On Earth: Last Poems and an Essay in April. Later in the year, Bob’s 1982 Collected Poems will be reprinted with a new cover as Volume 1 of the new Collected Poems, and a new Volume 2 will include all the work from 1975-2005.

Goodbye, Bob - and, as you liked to say, Onward!

Update: an earlier article on Creeley, written in 1978, is now posted here. On Earth is now available here, and the second volume of the Collected Poems here.

(An earlier version of this text appeared in last fall’s Asheville Poetry Review. Thanks to Keith Flynn for permission to republish it here. Thanks to Jonathan Williams and the Black Mountain College Museum + Art Center for permission to use Jonathan’s photograph, “Portrait of the Artist as a Spanish Assassin”, taken at Black Mountain College.)

Labels: poems, poets, Robert Creeley

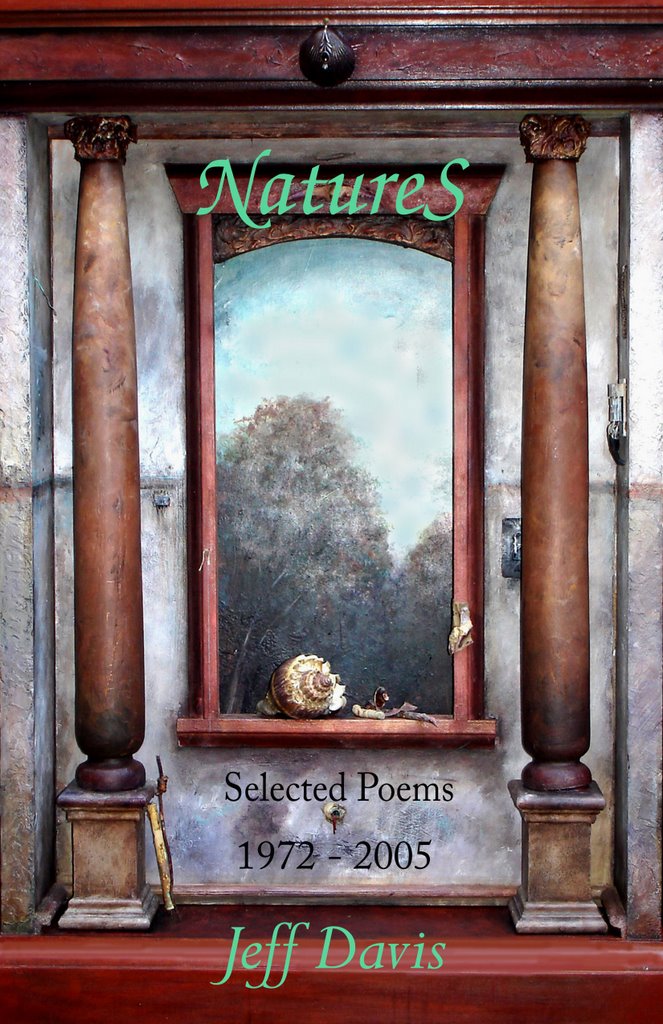

No news from the printer for two weeks, which presumably is good news, since they've been quick to get in touch when there've been problems with the files for the book. So ... it's hopefully done. I think another round of copy editing would have been a trial.

No news from the printer for two weeks, which presumably is good news, since they've been quick to get in touch when there've been problems with the files for the book. So ... it's hopefully done. I think another round of copy editing would have been a trial.