A note: the desktop computer is down again, waiting on another mainboard, and much of the material I'd like to work into posts resides on its internal hard drives. While we wait, here's a piece I wrote on Robert Creeley in, I believe, 1978. I had just met him again, after some four or five years, at a program on Black Mountain College that was held at Warren Wilson College, located east of Asheville in Swannanoa, not too far from the original Black Mountain campus.

The article first appeared in the Arts Journal

, though I'll have to track down the volume and issue numbers.

[3/26/07 Update: Located a copy of the old Arts Journal; the piece appeared in June, 1978, in Volume 3, Number 9, on page 30.]

A much later (though posted much earlier) consideration of Creeley and his work can be found in the archives here.

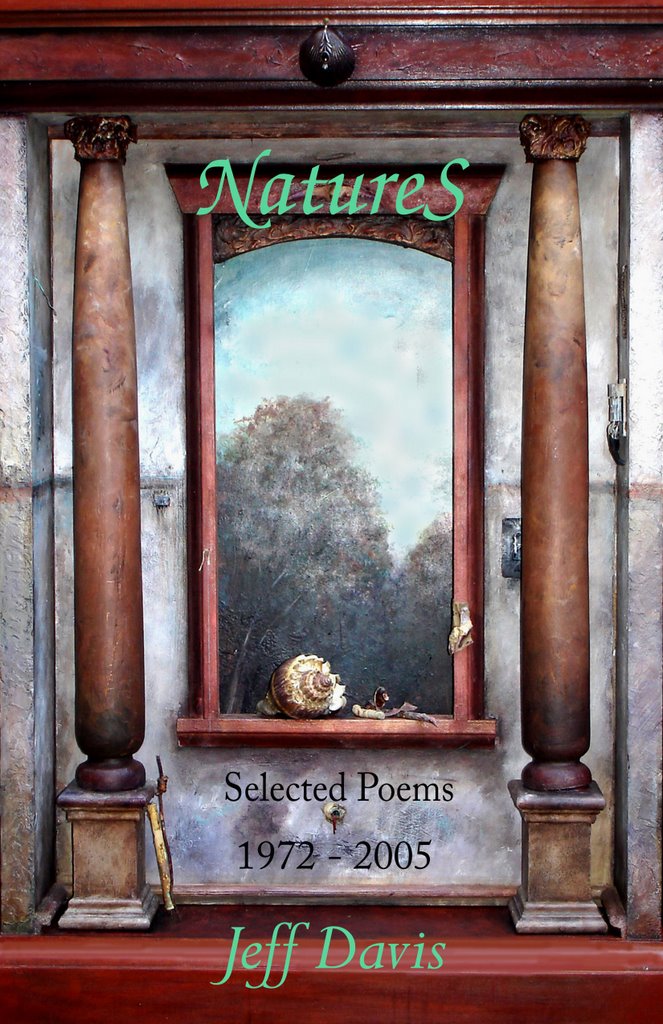

The photo, by Joel Kuzai, finds Creeley at home in Providence, RI.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

First, some observations by Creeley concerning Black Mountain College (where, of course, he taught) which institution furnished posthumously the occasion for Warren Wilson's recent course, and his own visit there:

Black Mountain was more than a college. It was actually a collection of real people.

It wasn't trying to save the world. ... The one real dilemma of that reality was that the world wasn't finally there, although people lived and died, tried to commit suicide, put themselves in extraordinary intellectual and existential patterns, but somehow the world was absent. .. . There was an inexorable sense of practicing for the world ... One thing now in retrospect is that extraordinary rehearsals did take place - Black Mountain was an extraordinary rehearsal of possibilities.

That was its intellectual wonder.

The awful hostilities of the situation I won't rehearse for you, the fading grandeur of Black Mountain now shrunk to twenty-five persons, momently to shrink to twelve enrollment, the great intellectual authority of that situation. The nation waits, the world waits, the FBI waits, the State Board of Health awaits ... You didn't have to worry about who was watching you, because there they were.

. . . Have you ever had a college in which there were no students?. . . I remember being in this faculty meeting when the enrollment for the subsequent term was nil, there were no students and we had to say why we were going to continue as an educational facility.

. . . No students, no college.

I'm not at all here to celebrate the isolation of an educational pattern within a social autonomy or reality that has no use for it. My proposal is that insofar as we are human, and we are, insofar as we continue information variously collected, and we do, that sudden flashing moments ... exist for an instant in time, they inform the individuals that collect in that pattern, but the hierarchy of their information is paradoxically of no value, except to the persons present. In other words, there's no way of translating that information apart from the experience of it.... There 's no substitute for being there.

. . . But, you know, the authority of being here and now is that you are here and now.

Creeley's comments not only help locate Black Mountain as an event, but speak in terms of a particular context from the sense of world he has recently encountered also in his poetry. And that poetry is, for me, the stuff that matters.

His work has sometimes been misunderstood as merely solipsist. No doubt he is a person of considerable privacy, with a tenacious sense of the singular aspects of consciousness, but he is also so attentive to the exploratory turns language does take, to open speech to the world, of others, that such qualification seems strange indeed. As Charles Olson noted in a letter to Cid Corman, editor of the wonderful magazine

Origin:

in the very interstices of sentences,

be can breathe and feel out all that

is worth beating, worth grabbing on

to, of another man.

Or, of himself, his own speech. Of that, his poems are evidence enough.

It is possible, though, to see in his work where such a term might have found some apparent ground. Early, in "The Dishonest Mailmen" (from

The Whip, 1957, and subsequently

For Love, 1962) for example, he writes, in definition of the sense of audience his work addressed, and the necessary task of imagination (I give the whole):

They are taking all my letters, and they

put them into a fire.

I see the flames, etc. But do not care, etc

They burn everything I have, or what little

I have. I don't care, etc.

The poem supreme, addressed to

emptiness - this is the courage

necessary. This is something

quite different.

The other poems in

For Love likewise speak with a solitary authority. They are sometimes occasional (in a fortunate sense), or addressed to specific persons, sometimes folding in presumably actual words and voices of others in dialogue and counterpoint; but they don't really specify the world, human or otherwise, in which they find their occasions. So it remains mostly uncreated as such - except, of course, whatever the occasion, one does get the activity of the mind, its feelings and its explorations of the situation via its language, which encounters and reveals sudden, bright instants. Olson, in a review of the book, spoke of "a generalized symbiosis of [Creeley] and those he places in the forged landscape," which still seems an accurate account of the activity of the poems, and Creeley's stance then in relation to the world.

Creeley's work since has presented a continual unfolding into a larger sense of world, an envisioning of such in its particularity. The poems (to speak quickly) through

Words,

Pieces, and

Daybook discover a wider address, and are immersed more and more deeply in a world of particular persons and occasions, to come to the always implicit other side of that initial singularity of address - i.e., the poem addressed to no one, but also to anyone.

When Olson dedicated the first volume of the

Maximus Poems to Creeley as "the Figure of Outward," it was a move that sprang from actual intuition of the necessary direction of Creeley's push - as his own, as any man's, who is serious. The glyph that accompanies the dedication is the silhouette of, perhaps a man cast like an opening net into the sky, the net of the mind in its elemental air. (Or, a piece of perforated tin ceiling, in some literal sense.) Olson, I would hazard, saw Creeley's struggle and triumph in this outwardness, and Creeley's persistent activity in this pattern gave Olson himself (though he had already ventured into Maximus) the companion and foil he then needed to extend into the reaches of his own world.

The Maximus Poems became Olson's plunge.

Creeley, having offered Olson a primary recognition of the possibilities of this activity has now, it seems, followed its trajectory into new dimensions of his own world. That world's locations (e.g. West Acton, Mass.) and persons are now actualized in fuller particularity of the occasions they present, present, than in previous work. And the gain, of course, gives a more actual presence of voice also, a new range of tone.

"Form is never more than the extension of content," Creeley long ago said - extension, tension, from Proto-Indo- European

ten, a stretch, out against the resistance any motion meets to the equilibrium between the movement and the inertia it discovers in itself, and beyond itself. A dancer makes form from the limits of his/her human power against simple gravity, as well as from space. Accuracy and grace of movement return some strength to him, to the dance.

“One thing, for an artist at least," Creeley observed at Warren Wilson, "is to keep particular to the body state, to the information of being person."

The poems which move to address no person as such find a language that, in a concern to be equal to many situations of meaning, wakes resonance not previously heard in their spare words. I think of "The Plan is the Body" (of the

Selected Poems), or a poem read at Warren Wilson, “After”:

I'll not write again

things a young man

thinks not the words

of that feeling.

There is no world

except felt, no

one there but

must be here also.

If that time was

echoing, a vindication

apparent, if flesh

and bone coincided –

let the body be.

See faces float

over the horizon let

the day end.

Or, the conclusion to one passage of another, “Later”, which turns to include the speaker in the double predicament, keeper and kept:

there's more always here

than just me, in this room

this attic, apartment

this house, this world

can 't escape.

"The descent beckons/as the ascent beckoned”; so W. C Williams discovered. It beckons one into the self and into the world, to make light of both. As Creeley says:

… now the wonder of life is

that it is at all

this sticky sentimental

warm enclosure,

feels place in the physical

with others,

lets mind wander

to wondering thought,

then lets go of itself,

finds a home

on earth.

For me, having met Creeley's work anew, there is new certainty that the reports of this voyage his work offers will be of real use, a delight, as I follow the consequences of a common morphology here, and now, and beyond, on the path home.

Labels: Black Mountain College, Black Mountain poets, poets, Robert Creeley